Have you ever felt fatigued just looking at those headlines screaming how the world is getting worse? Have you ever despaired imagining what kind of a world will we leave for the next generation? Have you ever had that heavy dragging sense of despair as to what the world is coming to? Then, Factfulness by Hans Rosling is a must, must read book for you.

In case you are curious about the book, one look at the subtitle tells you what it is all about – 10 reasons why we are wrong about the world and why things are better than you think. And yes, this title is not at all exaggerated. If you don’t believe me, check out this wonderful review written by Bill Gates for the book.

About Hans Rosling

Hans Rosling was a Swedish physician with a wide varied experience across the world, including providing expertise on limiting the spread of Ebola in Africa. He was particularly interested in the shifts in development indicators (not just economic) around the world like population, education, health care etc. He was also fascinated with bridging the gap between data showing development and most of us choosing to see doom and destruction.

It is this passion which made him set up the Gapminder Foundation in Stockholm with his son and daughter-in-law. Another way in which he intended to promote the knowledge of positive development indicators which most people choose to not see was his work on the book in question – Factfulness.

Unfortunately, he passed away in 2017. As I read the book, my only thought was that he would have made for such an important strategic ally as the world teams up together to fight the coronavirus.

About Factfulness

While I finished the book some time back, as I flipped through the notes for the purpose of this post, I marvelled once again at the depth of his thinking. The book, Factfulness starts off with a quiz on some basic metrics about the world like poverty, education, climate change etc and how far have we made progress on those metrics. Spoiler alert, most people get the answers wrong with a warped view of how bad the world situation is. Before you say fake facts, all statistics are taken from published United Nations numbers. Take a sneak peek of those facts with this fantastic 5 minute video done by Rosling for BBC back in 2010.

The rest of the book is the really interesting part where Rosling details out about 10 instincts that he has identified which hamper us from seeing, seeking or retaining the correct facts. If you are even the least bit self aware, you will identify all those facts with yourself in some situation or the other. The great part is that with each of those instincts, Rosling also gives us some very actionable ideas about how to avoid those traps.

5 Reasons why we are wrong about the world

In this post, I will limit myself to giving a brief idea of five of the ten instincts outlined by Rosling along with the ways recommended by him to consciously avoid falling for those.

Gap instinct

“Factfulness is … recognizing when a story talks about a gap, and remembering that this paints a picture of two separate groups, with a gap in between. The reality is often not polarized at all. Usually the majority is right there in the middle, where the gap is supposed to be.”

-Factfulness, Hans Rosling

Gap instinct also helps to build vivid pictures of difference and in a way polarise the world. But, no one does a better job of describing the most important aspect where this instinct really makes it’s presence felt than Rosling.

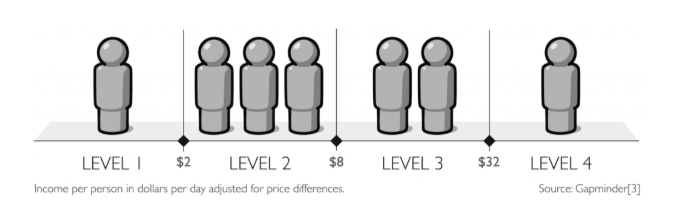

For years now, we have been used to dividing the world in to developed and developing / under developing countries. Rosling tells us that it is the most striking example of gap instinct at play. He recommends replacing that idea with 4 income levels which can be universally applied across the world. In that case most countries will have a mix of multiple levels. Most importantly, when you see the image below, you see that majority of the people fall in the middle rather than at the two corners.

Source: Gapminder Institute

Rosling suggests three ways to check yourself for tumbling in the chasm of the gap instinct:

1. Dig deeper into averages

Averages can be mean (Okay sorry, this pun begged to be cracked). On a more serious note, while averages are useful they often hide range and the variation of a data set. For instance the average of 6 and 34 is 20 and so it is for 18 and 22. So while there is really a gap in the first instance, there is barely any in the second.

2. Are you focusing at the edges?

Sometimes we come across the extremes – the richest man on earth or in asia, the poorest of poor. However, that fails to take into account that the majority may lay somewhere in between. So it is with other data set too. When you look at only the outline, the colour filling that shape in gets ignored.

3. The view from above

When we see something from a height, everything looks like little distorted specks – trees, cars, houses, what have you. Most of us who have the luxury of thinking of the world beyond our four walls belong to the highest level or Level 4 of income. From our heightened perspective, everyone below it looks the same and distinctions between the levels blur.

Negativity instinct

“Factfulness is … recognizing when we get negative news, and remembering that information about bad events is much more likely to reach us.”

-Factfulness, Hans Rosling

Rosling points out to three possible reasons for why we might fall for this instinct. One, we generally view the past with rose tinted glasses. Remember the refrain of “good old days”. Sure, there would have been good aspects to the days of yore but our instinct of painting it with a wide brush of positivity does injustice to the present and to the possibilities of the future. Two, negativity catches our attention and our brain mulls over it much more than the positive. This fact is used by journalists and even activists who want you to feel and act on the cause they are passionate about. Third, which I found most insightful is this muddled feeling of conscience and guilt. If we think things are still bad, believing they could be getting better makes us feel “heartless”.

The loss of hope is probably the most devastating consequence of the negativity instinct and the ignorance it causes.

– Factfulness, Hans Rosling

Rosling suggests remembering the following four factors in mind when you try to look at the world around you. I think they are especially useful when you feel you are drowning in an upswell of bad news.

1. Better and bad can happen simultaneously

If a situation is bad, it does not stop it from getting better while remaining bad. It’s just that the degree of bad may reduce. That is something to acknowledge and feel hopeful about.

2. Good news does not make for profitable news

Scan the newspaper, news channels or even online news. There is a high chance that you will come across much more of the bad news, be it scams or crime or accidents or natural calmaties. While these things are actually happening in the world, there are enough good things that go unreported because if the human proclivity to bad news.

3. Snails don’t make news

When we talk about such big metrics of human race, changes also happen at a snail’s pace. No wonder it is often data over decades that helps make sense of progress. So yes, we as a race may be progressing continuously but the slow incremental growth is not something you will get to know or even appreciate.

4. Recognise the media intrusion in our lives

Till a few decades back, we were used to only one or two half hour news bulletins in a day and had to wait for the newspaper the next day. Compare this to today when breaking news reaches you either through app notifications or whatsapp groups before you can even say what! Not just that, it is used to feed the never-off cycle of news on the 24-hour channels. Now, in this scenario if you see more suffering, know that a lot of it was probably much worse earlier too but was never noticed or publicised.

Size instinct

“Factfulness is … recognizing when a lonely number seems impressive (small or large), and remembering that you could get the opposite impression if it were compared with or divided by some other relevant number.”

– Factfulness, Hans Rosling

For me, this was one of the most useful instincts pointed out by Rosling, that works very well for almost any data that you could come across. Do not look at a number in isolation. Especially when it is a big number, it has a tendency to awe and overshadow or hide more relevant aspects.

Also, Rosling makes an important distinction of how relative numbers or a rate may be a more vital indicator than simply a gigantic number with many digits. He has three suggestions for checking this instinct of awe with size:

1. Everything is relative

Always look at a number in context. As Rosling rightly points out, lonely numbers should raise all possible hackles. You can compare it over time or across peers or just any other comparison which helps you make better sense of the number.

2. Remember the pareto principal

The pareto principal is one of those rules of thumb that can be applied for almost anything in life, whereby 20{76b947d7ef5b3424fa3b69da76ad2c33c34408872c6cc7893e56cc055d3cd886} components can be attributed with 80{76b947d7ef5b3424fa3b69da76ad2c33c34408872c6cc7893e56cc055d3cd886} of the results. The same can be applied to numbers also, especially when there is a long list. Check for the biggest or even the most conspicuous numbers to tell you the main gist of the story.

3. Rate is important

With any number, scale can be only known as a rate. For instance, recently there was a report that with 102 billionaires, India now has the fourth highest number of billionaires in the world. But, that still makes it less than one per billion in a population of 135 billion. That rate would push it behind many of the other countries in that list.

Generalisation instinct

“Factfulness is … recognizing when a category is being used in an explanation, and remembering that categories can be misleading. We can’t stop generalization and we shouldn’t even try. What we should try to do is to avoid generalizing incorrectly.”

– Factfulness, Hans Rosling

In this day and age when there are so many conversations around racism and negative biases, it is useful to try and not generalise. In India, we anyway do so. South Indians are geeky and smart. North Indians have street smarts. (See, how I smartly said only the positive aspects 😉 )

Rosling comes up with the following suggestion to keep this instinct in check:

1. Groups are not homogeneous

A group is made up of many elements and all of them do not exhibit the same characteristics even if they have some similarities and are often grouped together. For instance, in India we often feel all countries in Europe and North America are rich but we may actually be better off than some.

2. There may be similarities across groups

For instance, I think there are cheats within all possible categories of humans – men, women, children, whites, blacks, browns, tall, short. You name the category and you will find similarities. Hence, do not tag an instance or trait to a particular group when it could as easily transcend the category.

3. Yet there may be differences between them

Looking at similarities in no one hints at painting the entire world with the same brush. Be mindful of the differences and view things on their own merit. If this sounds confusing, you know you need to read the book because Rosling does a much better job at it.

4. Dig deeper behind “majority”

The word majority is thrown around easily although it encompasses a wide range from a fairly meagre 51{76b947d7ef5b3424fa3b69da76ad2c33c34408872c6cc7893e56cc055d3cd886} to maybe even a 99.99{76b947d7ef5b3424fa3b69da76ad2c33c34408872c6cc7893e56cc055d3cd886}. In this range, the picture could be very different.

5. Beware of outliers

Often the media likes to parade the outliers for the shock and awe it can cause. For instance the richest man. Remember these are only the striking vivid examples and the category extends beyond that one shining example.

6. Give the benefit of doubt

Most of us humans are narcissists with an inherent us vs them instinct. We like to believe everyone else who does not fall in the categories privileged enough to have us as members are idiots. Try to assume the opposite while operating in the world.

Single perspective instinct

“Factfulness is … recognizing that a single perspective can limit your imagination, and remembering that it is better to look at problems from many angles to get a more accurate understanding and find practical solutions.”

– Factfulness, Hans Rosling

This is one of the biggest threats in our extremely polarised world where we live in our echo chambers. It also feeds into our brains weakness for craving simplicity and looking at the box through a lens of black or white. Instead, embrace the greys to realise that for almost anything, the cause or the effect or the result cannot be shrunken to a single narrative.

In this regard, I am so grateful for my training in history, during graduation. If you choose to study history from a credible source, you will learn the value of seeing the good and the bad in personalities, dynasties and events. You will begin seeing through multiple lenses and building context for things that you come across.

Rosling presents some valuable suggestions to dealing with falling for this instinct:

1. Seek disagreement

If you have formed an idea or an opinion in your head, actively seek out views that go against what you have in mind. With the right destination in mind, there is no better guide map than the internet with all data, content and facts that you may need to get there. But, most of us would rather prefer to confirm to a singular view and that too often influenced by peers.

2. Beware of expertise

If you believe or if you are an expert in a field, discard the idea that you would know every possible aspect of the field. Always be keen to learn. In the same vein, for a particular topic do not depend on that one expert. Seek out a multitude of voices for any subject.

3. Develop a multi-disciplinary approach

As Rosling puts it, if you have a hammer then everything seems like a nail for it to be used on. Instead, he recommends having toolbox with a variety of implements. In other words, go for a multi-disciplinary approach. In some ways, Charlie Munger and his idea of mental models also derives from this. When you seek information from varied disciplines, seemingly unconnected threads come together to weave a very different picture.

4. Numbers are critical but not enough

So often the world is divided into numeric person and a non-numeric person. You are either good with numbers or you are not. But, numbers are really a hygiene aspect to understand the world around us and shying away from them just leads us into a dangerous cocoon. On the other hand, numbers cannot tell us everything about the world. The world is also about individual stories and reading between the lines, or numbers in this case.

5. Treat simplicity with suspicion

If something seems too obvious or too simple, adopt my favourite question – what’s the catch? Remember no one explanation of reasoning for anything and definitely not for everything.

If you want to feel optimistically hopeful about the world as well as become conscious about some of our prevalent biases, this book is a must-read. As always, this post is only meant to whet your appetite and make sure you get hold of this eye-opener of a book.

Leave a Reply